Musings from 3 Months in Japan

I just spent three months in Japan with two friends, Eric and Tim. It was my first time really traveling outside of California, let alone internationally. I would have happily (read: lazily) moved on, without writing anything about it, even though my mom was hounding me to write. However, once I got back, my family friend Naveen, who lives in India, asked me about the trip. He said, “I would like to hear or read your words about what the experience was like. Because going to Japan for three months is just a notion to me, something I’m never going to actually experience for myself. But I’m very curious to know what it feels like, and the only way I’ll know that is if you tell me.” His words made me realize that it’s selfish of me to keep this experience for myself, especially since I won’t have the opportunity to talk about it personally with everyone I care about. So I’ll do my best to share here.

Naveen also told me something else that made a lot of sense. He said, “I’m not that interested in hearing details about the trip and what you guys did there. I’m interested in hearing what it felt like. What did you learn, what will you carry with you for the rest of your life?” So that’s what I’ll try to describe here. This account will be minimally about what Japan is like. Instead, it will be about what the visit meant to me, and what impression it left. I’ve also decided to write this in a personal journal style, since it’s tough work to distill three months of travels concisely. This means it will probably be lengthy, rambling, and meandering; I apologize in advance! But hopefully it will be a little more personal as a result. I think writing about this trip would also be good for me, since oftentimes we don’t really internalize an experience until we talk about it with others.

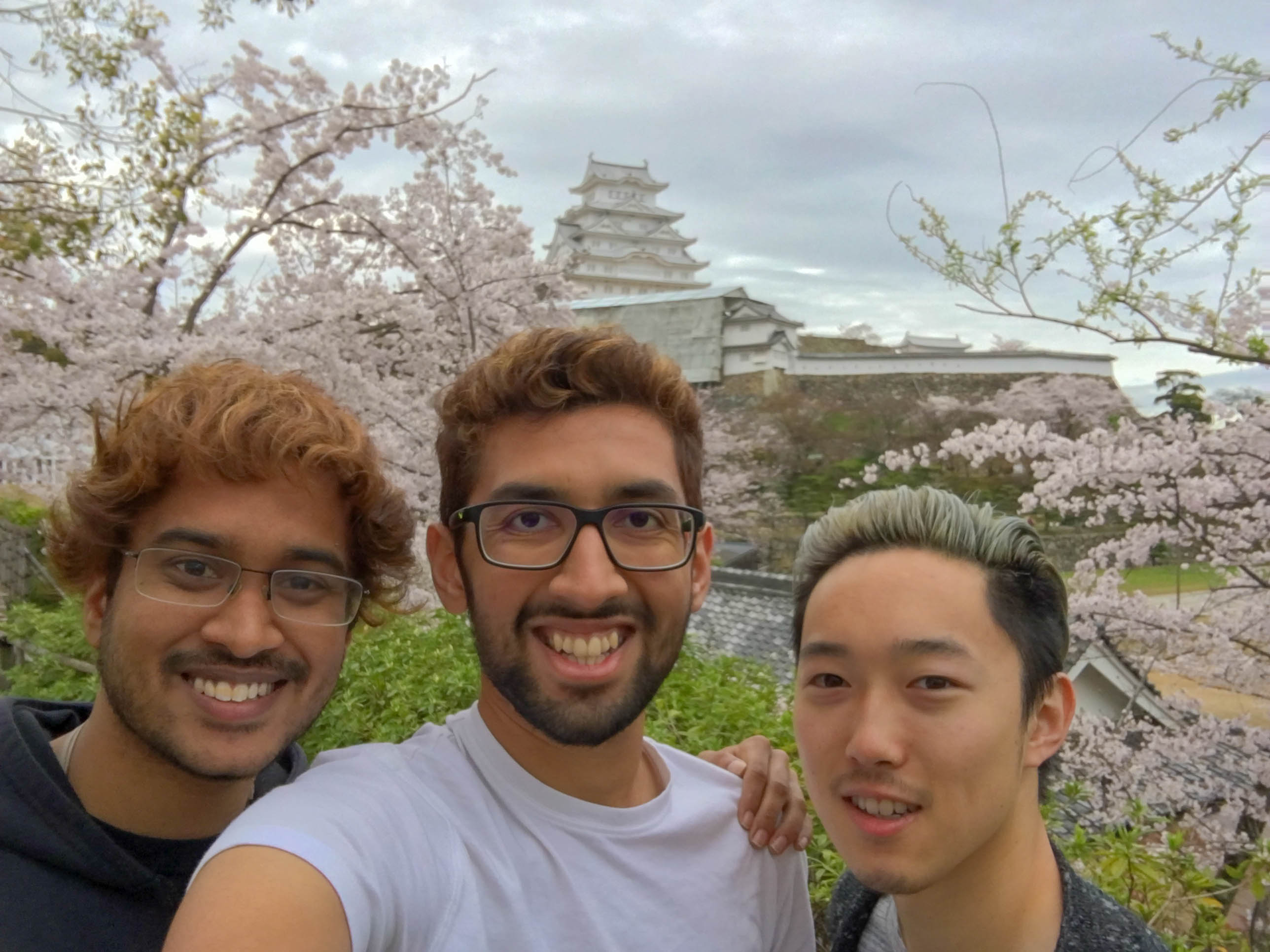

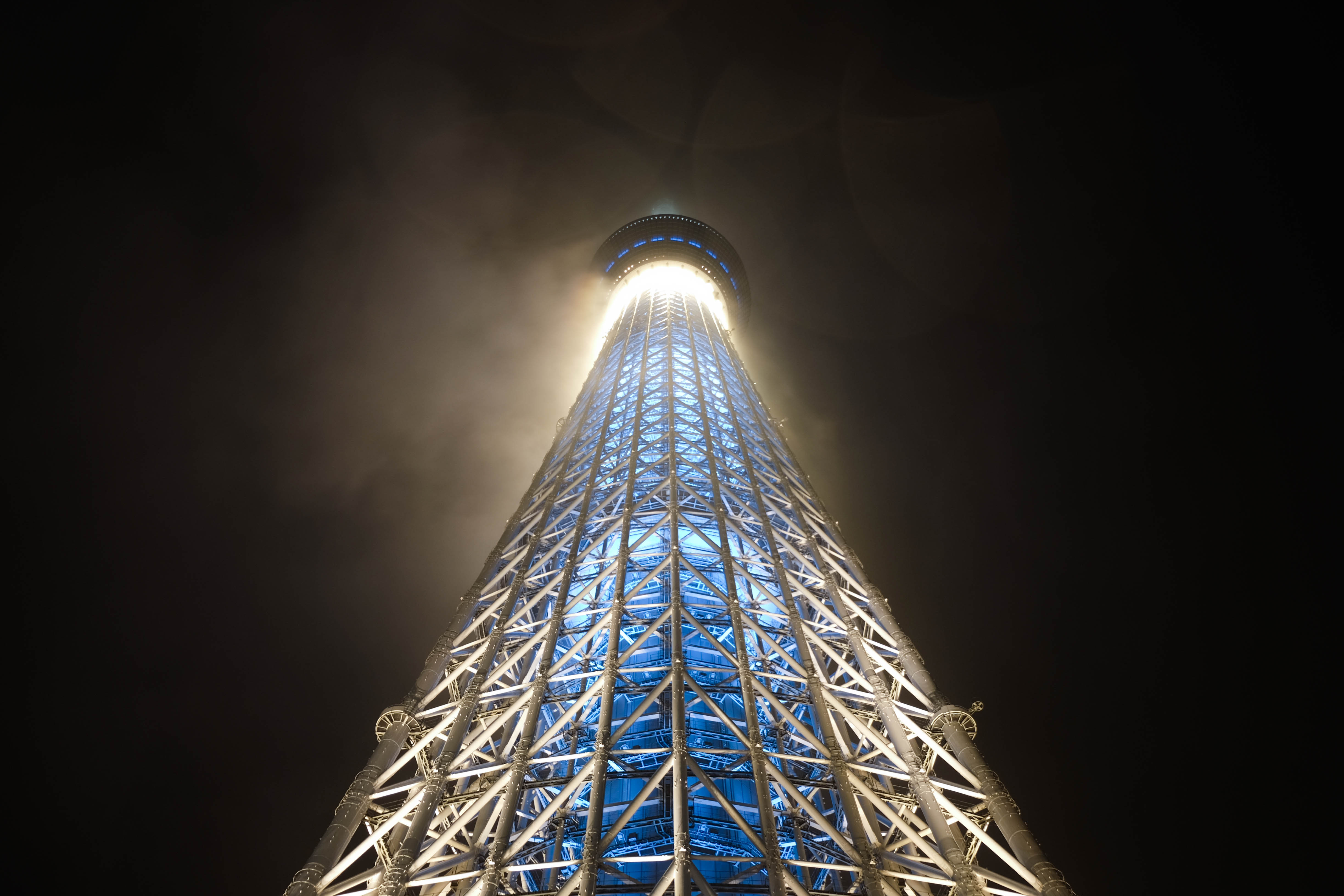

I’ll also throw in photos I took along the way. Hopefully they’ll set the mood a bit, and I can’t think of a better way to share photos of the trip with friends!

Here’s one, just to whet your appetite. It’s one of my favorites from the trip, demonstrating the artistic magnificence of the Tokyo Skytree building. Even though we got screwed by the rainy cloudy weather when we got to the top (we couldn’t see a thing), it was wonderful to see the beauty of the building itself.

The theme here is “takeaways”. So I’ll try to keep that context in mind while I describe the trip. The first takeaway actually happened before we even got on the plane.

The cost of growth

A month before we left for Japan, I quit my job as an AI researcher to become an independent game developer. This was a big decision for me, and I was already thinking about how unpredictable life is and what the future might hold. I also was thinking about how I need to be more minimalistic and flexible with my lifestyle, since I was now living off of savings and out of my parents’ house; the clock had started ticking.

Within a week of quitting my job, my long time friend Eric, who had encouraged me to become a independent game developer, took me out to lunch. He said, “I just got laid off, and it’s the best thing that’s happened to me. I got FAT severance pay, and I’m free to travel. We talked about going to Japan one day. That day is now. Get your passport ready, we’re leaving in less than a month.”

I was flabbergasted. Less than a couple months ago, I had thought I was going to be an AI researcher for life. Less than a week ago, I thought I was going to hit the grindstone and work distraction-free on my game for the foreseeable future. Now instead I’m going to Japan? For one, how would I even afford something like that?

Eric had an answer ready. “Money? Don’t worry about money for now. Are you in?”

How could I not worry about money? I would have to move out of my Redwood City place three months before the lease expired, and double pay rent. But if somehow money wasn’t an issue, then hell yes I was in. This opportunity may never come again.

Eric said, “Good. As for money, I’m willing to give you an interest-free loan for the full cost of the trip. I won’t let you pay a dime there. You can pay me back whenever you get income again.”

I was blown away. How could he offer something like that? And why?

His answer was simple. “You’re no longer tied down to a place, so travel is something I can actually offer to you. I’ve saved up more than enough money, so lending you this much is no problem at all to me. And I know that this experience is something that will be invaluable to you for the rest of your life, especially as a creative, so I want to give it to you. Think of this as my investment in an incubation program for your career as an artist.”

His selflessness and care for me touched me deeply. To have a friend like that is a blessing I will cherish my whole life.

Here’s the thing. I could have and was fully prepared to just get started working on my game, and try to make it good to the best of my ability. Instead, he was offering me a chance to learn more about the world, that too in Japan, the Mecca for video games and technological art culture. I was being offered time to think and introspect, which was going to certainly infuse depth into my future art. It wasn’t going to guarantee that I would create good art, but it was definitely going to improve the chances. I’m so fortunate to not only have the opportunity to pursue art and my passions full-time, something very few people get to do in their lifetimes, but also get to learn something about it through travel before I even get started working.

Naveen commented on this beautifully in our recent conversation. Talking to my parents, he said, “Creativity can only come when all our essential needs are covered. Only a developed society or family can afford to support their children enough that they have time to spend on being creative, because creativity does not bring food to the table initially. So consider yourself fortunate to be able to provide for your children and take care of their needs; through them you are fostering creativity and innovation in a way that few other people can afford to follow.” In other words, it takes a village to raise a child. And art is the mark of a civilized society, because without civilization, art cannot emerge. This whole experience made me so appreciative of my family, my friends, my “village”. Without them, I would have been forced to fend for myself, leaving no space to pursue art. I owe it all to them.

It also made me really think about the role of money in our lives. Without Eric’s money, this would not have been possible. He’d been working for others and saving up for years, and he’d finally found something worth spending that money on. Because he had money, he was able to go to Japan and take his friend along. It reminded me of my friend Maitrey’s words, when he was helping me budget the next year as a solo game developer. Instead of budgeting for material goods like the latest gadgets, which I had loved to spend money on, he told me to cut most of that budget and move the rest to events like concerts and trips. He told me, “Don’t spend on things; spend on experiences. Things are transient, but experiences leave lasting memories.”

Later during the travels, I learned another lesson about my relationship with material things that could only have come from traveling. But for now, we packed our bags and got ready to leave for Japan.

Before leaving though, we impulsively decided to get our hair colored. After all, when’s the next time we’ll be young and in Japan with colored hair?

Flexibility and resilience

One of things I wanted to find on this trip for myself is flexibility. I’ve always been someone who needs comfort, predictability, and control. I’ve been working on this for the last year, trying to be serene in any situation no matter the circumstances. But what better way to practice this than while traveling? You don’t know where you’ll be sleeping or what you’ll be sleeping on, what you’ll be eating, how long you’ll be moving around. So I focused on being happy through the whole trip, avoiding complaint or stress. One thing in particular tested this attitude a lot: the food.

Frankly, if you’re a vegetarian, the food in Japan is just not going to work. Meat is the soul of food there. Fortunately, I’m not vegetarian, but I’m also not used to eating exotic kinds of meat. I hadn’t even developed a taste for fish before leaving. And Japan is huge on fish. So I had decided that as an exercise in being a flexible creature, I was going to learn how to eat almost anything while in Japan.

At restaurants, I would let Eric and Tim order, because they’re more open-minded with food and would order all kinds of things I would never have ordered myself. Sometimes, when there was no English menu, we would have no choice but to say to the waiter, “Omakase”, which literally means, “I leave it to you.” And they would bring dish after dish of random and inventive foods, which we would happily devour.

As someone who’s used to eating just basic meat, I ate so much crazy stuff. From raw pork to octopus legs and squid ink. Horse meat. Even jellyfish. I didn’t even know jellyfish were edible. But I put it in my mouth and chewed. (It was surprisingly tasteless, and the texture was simultaneously slippery and crunchy.)

In spite of it all, there was only one thing I could not even consider eating. At a conveyor belt hot pot place, we saw… wait for it… pig brain. Yes, raw brain that you’re supposed to cook yourself in your hot pot. I wouldn’t eat it, but I would like to say that if I absolutely had to, I would now probably be able to do it without throwing up. For me, that’s saying something.

Along the lines of flexibility, it was surprisingly comfortable to live in Japan. It’s very clean, considering the density of population, far cleaner than San Francisco or New York. And almost every single person was exceedingly nice. They didn’t speak much English, but when speaking to us, they would try, and we would try our best to speak the little Japanese we learned. In this way, we got by without using Google Translate much at all. It was super interesting to have to communicate with people who didn’t speak the same language. People were also fascinated with us, and surprised that as foreigners we were visiting Japan for so long. I had a long conversation with a Japanese family that ran a restaurant near where we were staying in Tokyo, and they were clearly so happy to talk to me. As an introvert, it was very refreshing for me to connect with other people who live such different lives from mine; this Japanese family consisting of husband, wife, wife’s brother, and husband’s mother spends every waking hour working at this tiny hole-in-the-wall, doing the exact same thing day after day. I can’t imagine that kind of life myself, but they are so happy.

The Japanese people are also extremely professional in everything they do. Their engineering is solid; for instance, riding the Shinkansen, or bullet train, was a trip. It’s unbelievably fast, and always perfectly on time. But the most shocking thing is that it is controlled by humans rather than machines. Highly trained humans with pocket watches that never make a mistake, always bringing their train on time. Pretty amazing.

We experienced this professionalism first-hand, when we messaged our Airbnb owner about our bathroom drain that had been clogged and was causing flooding when we showered. Within an hour of making the request, a young man showed up at our door. He was about our age, wearing a full black suit, and carrying a leather briefcase. We were confused; was he here as an agent of the owner, to inspect the bathroom or something? He greeted us, and walked into the bathroom. Then he carefully opened his briefcase and pulled out janitorial instruments. He rolled up the pant legs of his slacks, and manually unclogged the drain. Then he called us and proceeded to pour water for a full minute into the drain, unassailably proving that it was fully unclogged. Like James Bond, he left without a single mark on his pressed suit. The whole thing was absolutely astonishing.

Empathy beyond language

The language barrier showed itself most prominently to me when I tried to wash my clothes. One night, I went to the shared laundry and dryer machines on the roof of our building. When I got there, I found myself utterly lost. The laundry machine was full of buttons labeled with kanji, and I had no way to know which one to press. Unlike a human, this was a machine that would not try to meet me halfway. I won’t go into all the details of the experience that followed, but I will say that using this machine was a goddamned train wreck. I spent over 25 minutes just to get it started, and once the load was complete, I couldn’t figure out how to get the machine opened, so I accidentally triggered it into doing another full cycle. The whole process of getting my clothes washed took over 5 hours, during which I couldn’t go to bed.

This experience really made me think about what life must be like for an immigrant to America, like my parents were. At least my parents could speak English; what about all those people who can’t? Is every experience using a machine like a dishwasher, something that’s so easy for me that I don’t even think about it, a tedious and frustrating task? It opened my eyes to the reality that plenty of people in the world aren’t Americans, and don’t speak English like I do. And yet with the emerging global economy and culture, we’re going to be interacting with each other more and more. The only thing that will make this a happy experience is empathy for each other, something I had a small taste of in a foreign land. The world is both bigger and smaller than I originally thought.

Natural beauty

We saw beautiful thing after beautiful thing. We optimized our trip to coincide with cherry blossom season. Cherry blossoms are my favorite flower, and I was fulfilled to see the most cherry blossoms I’ve seen up to that point in my life combined. The density of blossoms in an area was spectacular.

Of course, most of the people there saw it as ordinary, having gotten used to the sight. I think tourists are naturally more likely to truly appreciate the beauty of a place than residents. I mean, look at me. I’ve lived in California for most of my life, and I still haven’t seen Yosemite. It’s so easy to take these things for granted. So it was definitely great to be a tourist in Japan.

They bloomed for only a couple weeks in April. They fell off in a wondrous shower of petals as soon as they had come. One day while gazing at them, Eric described why he loves cherry blossoms so much. “Only once a year do we get to see cherry blossoms. There is a finite number of years in your life, a finite number of times you can see them blossom. Miss a year? It’s done, that’s one of the few opportunities to see blossoms you will get in your entire life. We like to view the sakura bloom as a symbol of spring, of new life and new love. But they remind me that I will die one day; that with one gust, my life will be scattered to the wind, among many others. No one remembers the single blossom, and I will be forgotten. All that remains is the memory of a beautiful season, and a foolish, but lovable species. It’s up to me to make the most of this limited time I have. There is a Latin saying: memento mori: it means, remember death. Remember that you are mortal. Carpe diem, seize the day.”

Among the spiritual experiences of this trip, sakura (cherry blossom) viewing was definitely up there. The best view of them was at Himeji castle, a sight I will never forget. At night, a different spotlight was lit up under each sakura tree, coloring them like in a dream. Unfortunately I didn’t have a DSLR with me at this point, so I had to take the pictures on my phone. But you can imagine how gorgeous the scene must have been in person.

The Japanese really know how to make the most of natural beauty. It was very inspirational to me, especially as an aspiring game developer.

Walking and pondering

During this trip, I discovered the great enjoyment of walking. On days that we were traveling as a group, I would just leave the house, pick a direction, and walk alone for miles. When I got tired, I would turn around and use navigation to get back home. This way I saw a lot of Osaka, Tokyo, and Kyoto. I saw how people live and work.

It was also an excellent time to think and introspect, with the walking theta waves washing over my brain. I had a lot of time to think deeply about my game, and what I want to make as a game developer. My latest game idea has changed quite drastically as a result; spending literally weeks just thinking about it has really helped crystallize my thoughts around what I want to do with it and what I want it to become.

Traveling with two other game developer friends, I also learned a lot about the art of game development through conversations with them. One day, after staying up until sunrise, Eric and I went for a walk along the Sumida River in Tokyo. During this time, I was deeply rethinking what shape my game should take, so I asked Eric many questions that I’ve been having about how to make good art. He had perfect answers for me.

We talked about minimalism, as a result of me asking whether I should just be trying to make the simplest game possible and aim for Apple featuring or viral success, like so many super basic games out there that have struck gold. He told me:

“Minimalism is an illusion. You’ve been lied to, when you’ve been told that you should strive to make something simple. Good art isn’t simple, it’s extremely complex. It’s trying to convey some deep meaning, something with a lot of substance. Minimalism is not in the content, it’s in the presentation.

Don’t make something minimal for the sake of being minimal. Instead, take a complex idea, and present it as something simple so people understand it. If you start with something simple, what you make won’t have any substance, any meat to it. It’s easy to make something soulless. What you must do is to start with something complex, and slowly turn it into something easy to digest. That’s really hard, and that’s where the magic lies.

Take Journey, for example. Is it a simple game? You might say, yes, it’s so minimal. But look deeper. It’s a game whose purpose is to get someone to come to terms with death. That’s a very complex thing, perhaps the most complex thing a human can face. But they spent years working on it, past the point of bankruptcy, to turn that complex idea into something simple that any player can accept. That’s a good piece of art.”

Without this time to ruminate, I’m sure I would have been able to work hard and make a decent game. Even with this time there’s no guarantee that it’s actually going to be a great game. But there’s no denying that this time spent walking around Japan and just thinking is going to be invaluable in the game’s growth and my own growth as a game developer. I consider myself fortunate to have had the time to think than just blindly execute, all thanks to the people close to me.

The longest walk I did was in May, when I went for a pilgrimage walk on the Kumano Kodo. This is a UNESCO World Heritage pilgrimage, a serene multi-day walk through the forest. I decided to walk this path by myself, since I had spent the rest of the trip in the company of Tim and Eric, and I figured that a solo hike through the woods would be an unforgettable experience. Indeed it was.

Until this point, I had never been away from civilization for even a few minutes. I had always been around other people, in the comfort of technology, close enough to call for help if necessary. This was the first time I actually went to the forest and walked alone, kilometers away from other people, in the presence of bugs and snakes and animals. I walked for over 14 hours over the course of two days, staying at local towns at night along the way. The forest was absolutely gorgeous; I think pictures will speak louder than words here.

It was also a good opportunity to see the Japan countryside. To see the side of life that I’m so far from normally was sobering. Terraced rice fields were like mirrors of water reflecting the sky, and the blue roofs of houses shone like sapphire in the sunlight. And all along, I had plenty of time to reflect.

I felt really empowered during my hike. This was the first time I got to prove to myself that with preparation, I could indeed survive a hike alone out in the woods, something I could never be confident of before. I’m pretty damn terrified of insects, and during the hike I was constantly afraid of the Suzemabachi, the Japanese giant hornet. Those things are the size of your thumb, and if you get stung by them, you can die of their venom. Alone out there, I saw plenty of huge insects, including hornets, and every time one flew by me, I couldn’t help but feel like a prey animal. It was such a vulnerable experience to be out there, amidst nature in its raw form. But I survived, and it feels really good to know that I can.

Childhood

As for seeing a side of life I’m not used to, I had some great experiences during our stay in Kyoto. We lived in a very residential area that was pretty far from the rest of the city. One day I was walking to the nearby river for an evening stroll, and I passed a bunch of kids playing on the street. Without apprehension, they all excitedly came up to me and started asking me questions in Japanese. It was tough to communicate with them, because they knew even less English than the adults there, but I told them where I’m from, and how long I’ll be staying there. The last question they asked me in Japanese, which we all struggled to translate, was: “What color do you like?” I smiled and thought about it for a second, and said “Blue.” One of them happily showed me the ball they were playing with, which was bright blue, and asked, “Like this?” I said yes, and asked to hold it. Then I made a motion like I was going to throw it, and they all ran back. I threw it high in the air, and they clamored to be the first one to catch it. It was wonderful to see kids actually playing outside, something I deeply miss about my childhood, now living in a technologically ubiquitous environment.

When I told this story to my fiancée Kasturi, she asked, “How does it feel knowing that you’re making video games, an industry that is discouraging kids from playing outside?” My answer was that every new technology is a tool that you can use well or poorly. Too much of anything is bad, but in moderation, video games can be a powerful way to broaden your horizons and gain valuable, unique experiences that you can otherwise never have. You can play video games, and you can also play outside. It doesn’t have to be one or the other, and it’s up to you to find the balance. So I hope that the kids that play my games will also spend time together outside, like my friends and I did when I was young. I love the advice that Shigeru Miyamoto, creator of Super Mario and other legendary Nintendo games, signed in an autograph to an 11-year-old boy: Play outside on sunny days.

Inspiration

I was surprised to find how rich the game developers’ scene is in Kyoto. We were invited to a barbecue party by Liam, a game developer I met at the Game Developer’s Conference in SF before we went to Japan. The party was full of game developers who work in Kyoto, most of them foreigners who moved to Kyoto with their families a long time ago. It felt like a small island in Japan in which I felt like I was back home. To be able to speak in fluent English with someone was a luxury.

In the evening, many of us collected at the soundproof music studio they had on the bottom floor, and we jammed together on the variety of instruments there. It was very inspirational to me as someone interested in music, to see how talented people are, and how awesome it is to listen to them play live together in improvisation. After most of the brilliant musicians played and left, I got on the piano to play together with the remaining people. It was exhilarating to play music with strangers, creating it from thin air, even though I wasn’t very good. This experience inspired me to try my hand again at electronic music production, something I’ve been interested in for a long time. So the next day I started on my first remix, a remix of the song Sleepless by Flume, and I finished it after several days of work. Even though it was amateur work, I can’t explain how fun it was to make a complete song from scratch with just my hands, ears, and my computer.

You can listen to it here: Sleepless (Remix).

This collective musical experience was very inspirational to me as an aspiring musician, and made me realize that I oftentimes need other people and new experiences to find inspiration and motivation to pursue something I love. I was lucky to have found that experience during our travels, and I can’t predict how it might impact my life ahead.

In fact, this piece of writing is case in point. I’ve wanted to write for pretty much my whole life, but I can never seem to get down to it. It’s always a chore, and writing fiction feels like I’m just constantly bullshitting. But with the help of a trip to Japan, and a few persuasive people, I was finally inspired to write again, and I’ve never written a longer or more heartfelt account. I just sat down and blasted out almost 6,000 words over a few hours, and somehow it felt effortless.

When I spoke to Eric, a long time writer, about how fun and easy this piece was to write, he said, “The thing that is different about this Japan writeup versus previous fiction you’ve written is that you have a very, very solid experience in your head that you want to share with the reader. That’s why I always advise people to find the experience they want to share before they write anything. Fiction is actually very easy to write once you have something worth writing about.”

I finally have a renewed understanding of how to approach writing, and I have Japan and a few encouraging people to thank for that.

Things

A huge takeaway for me revealed itself in the form of packed bags.

We moved from one city to another three times during our trip. Each time, we had to pack everything we had into our bags. And each time, I would finish packing my bag, and then stare at it. This one bag contained everything I needed to live. I could live fairly comfortably for three months with just the things in this bag. In fact, I was carrying even more than I needed; two dress shirts, one pair of shorts, and a couple other things ended up not being used even once. Of course, I would have loved to have the many luxuries I had left back home, but this packed bag showed me that I didn’t need them.

This sat heavy on my mind especially since before leaving for Japan, I had been deeply analyzing my budget, trying to cut the fat so as to survive for as long as possible with a meager lifestyle, to be able to freely work on my own games. The more efficiently I could live, the more likely it was that I could turn my passion in games into a sustainable career. This was a sea change from my attitude towards money before I quit my job; with the stable income of a software engineer, I had been promiscuous with my spending, buying anything I wanted. Even though my fiancée always rebuked me for nonsense purchases that I barely ended up using anyway, I had no compelling reason to be wise with my money until the day it became the sole determinant of how long I could pursue my passion.

When I moved into Redwood City last year, with my three high-school friends, I thought we were going to live there for years. I believed this so much that I went out and bought a $4000 memory foam bed. Yes, a four thousand dollar bed. As a 25-year-old, this was totally unnecessary. Don’t get me wrong, it’s an amazing, amazing bed, and I love sleeping in it every night I can. But for the last three months, I didn’t sleep in it once, and later this year I plan to travel with my fiancée as she does her fourth year medical school rotations, so I won’t be sleeping it in then either. Who knows where I’ll be for the next few years? Was this bed worth it, if I’m not even going to be around to use it? If I had instead bought a thousand dollar bed (which is still pretty damn good), the remaining $3000 could have been stretched into several months of runway for my game. The ironic thing is that I didn’t even manage to live in the Redwood City house until the year-long lease expired; I moved out three months early in order to visit Japan.

My attitude towards possessions was ridiculously misguided before I decided to quit my job. It was rooted in a misunderstanding of my future; I thought I was going to be comfortable and settled down, living a predictable lifestyle. Considering I’m in my 20s, this is a silly expectation. This period of my life is the time to explore the world, get my hands dirty, work hard and relish discomfort. This is far from easy, but it’s the only way to build lasting character.

So when I got back to my parents’ home after Japan, I moved the few things I actually needed from the packed boxes in the garage into my room. These things had taken up less than half of the boxes. Now, if only these few items were what I was actually going to use, what’s all that in the remaining boxes? Why the hell do I have this much stuff I don’t need?

Having moved so many times in the last few years, I realized that all this unnecessary stuff I’ve accumulated has drained my money and weighed on my mind every time I’ve had to move it. I’ve always justified keeping it with, “I might use it someday.” But is it really worth it?

A TED talk about minimalist living that I saw last year came to mind. In it, the speakers were talking about something called a “packing party”. At this “party”, you pack all your stuff into boxes, as if you’re moving. Then you unpack each box, taking items out of it one by one, and categorize the item. If it’s something that you’ll use now, you put it where it belongs in your room. If not, either sell it, donate it, or throw it away. There’s no category titled “will use some day”. That’s just something you don’t need, so get rid of it.

I decided to do this with my remaining boxes, with an additional category. Anything that gives me pleasure by virtue of me possessing it, like a photograph or books that I collected, I’ll pack into boxes and keep them in storage. I don’t have the heart to get rid of those kinds of things. But everything else has to go.

This is a lesson I could have only got by traveling. Having to move from place to place forced me to consider the line between things I need and things I don’t. Even though it’s really hard to surrender luxuries and comfort, and I doubt I’ll be able to actually do it as much as I should, it’s a valuable perspective to have gained.

Coming home

This ended up being much longer than I expected, and yet I know I’ve forgotten a lot that I could describe. But I’ll leave you with a few more pictures and a quote I like by F. Scott Fitzgerald:

”It’s a funny thing coming home. Nothing changes. Everything looks the same, feels the same, even smells the same. You realize what’s changed is you.”